‘Pass it on’ New organ donation Law in England:

What black, Asian or minority ethnicity (BAME) communities should do and why?

Sunil Daga 1, Rakesh Patel 2, Dane Howard 3, Kirit Mistry 4 & Veena Daga 5

1. Renal Unit, St James’s University Hospital, Leeds Teaching Hospital NHS Trust;

2. Nottingham Medical School, University of Nottingham;

3. Pharmacy department, St James’s University Hospital, Leeds Teaching Hospital NHS Trust;

4. South Asian Health Action Charity, Leicester UK

5. Department of Anaesthesia, Leeds General Infirmary, Leeds Teaching Hospital NHS Trust.

Correspondence to; sunildaga@nhs.net; twitter @sunildaga23

Keywords

Black Asian Minority Ethnic, organ donation, opt-out, transplantation,

Cite as:

Daga S, Patel R, Howard D, Mistry K, Daga V. ‘Pass it on’ New organ donation Law in England from May 2020: what black, Asian or minority ethnicity (BAME) communities should do and why?

The Physician 2020 vol 6; issue 1; ePub 11.04.2020 (updated v2)

Changes – incorporated figure 1 deleted as per Peer reviewer recommendation and minor corrections

Under Peer Review

(This article is published under post-publication peer review policy. If you wish to write a review of the article please email your comments including your full name, affiliation to editor.thephysician@bapio.co.uk A final version of the article will be published here and in print once the peer review process is completed)

Commentary

From 2020, a new legislation comes into force in the UK providing legal status to the concept of presumed consent, extending this from Wales. In essence, consent for organ donation will be assumed unless the donor had actively opted-out. For Black Asian and minority ethnic communities, there is a widening gap between availability of donors and those that are waiting on transplant lists. A particular stumbling block seems to be the denial of consent by next-of-kin, which appears to be disproportionately high. Exploration of the reasons behind such withholding of consent appears to be lack of information, myths, a lack of cultural sensitivity more than any religious decree [1-2]. Hence, this article will explore in depth the current scenario, the causes behind these disproportionate representation and leadership that community leaders need to take to improve the access to this life saving treatment option.

1. Chakravorty I. The Gift of life – Social and Cultural Perspectives on Organ Donation.

Sushruta 2020 vol 13; Issue 1; epub 24.02.2020 https://www.sushruta.net/vol13-1-mar-2020

2. Krishnan N, Modi K. Organ donation law and its impact on Black Asian, Minority Ethnic communities.

Sushruta 2020 vol 13: issue 1; epub 01.03.2020 https://www.sushruta.net/vol13-1-mar-2020

Full Text

The New Law

On 20th May 2020, new legislation governing organ donation will come into force in the United Kingdom (UK). Also known as ‘Max and Keira’s Law’ after Max Johnson, a young boy who received a heart transplant from a young girl named Kiera Ball who unfortunately passed away at just 9 years old, Kiera’s parents’ decision will change the landscape of organ donation forever [1]. In essence – consent for organ donation will be assumed unless the deceased had ‘opted-out’ or are excluded under the various criteria outlined by the regulation. Nevertheless, the legislation still retains a “soft” opt-out option since the ‘family’ will be actively involved in decision-making prior to organ retrieval, where objections could still be made.

There were 6,170 patients active on the waiting list for a lifesaving or life enhancing organ transplant in the latest UK National Health Service Blood and Transplant (NHSBT) Report [2]. In the year from April 2018 to March 2019, 400 patients died waiting for an organ while being on this list [3]. There are currently 25.8 million people registered under the current opt-in system [2] and donations from these enabled 3,941 recipients to receive a transplant in the same year. These comprised 2,399 kidney, 204 pancreas, 180 heart, 164 lung, 972 liver and 18 intestinal transplants [4]. The overall number of people, who die in circumstances where organ donation is possible, is relatively static at about 6,000 people each year (which is about 1% of deaths in the UK). Finally, despite registering for organ donation, the family of deceased patients is known to only give consent in 68% cases [5].

Why black, Asian or minority ethnicity (BAME) communities?

Kidney disease is common in South Asians including a higher proportion of patients from Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) communities developing organ failure. Higher progression among BAME patients is attributed to the higher prevalence of concurrent medical conditions such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension and obesity. Mortality rate due to kidney disease is also higher in countries where BAME patients have emigrated from [6]. The prognosis of kidney disease is also poor in BAME patients since <10% of at-risk patients are actually aware of their kidney disease/kidney function and consequently present late [7, 8].

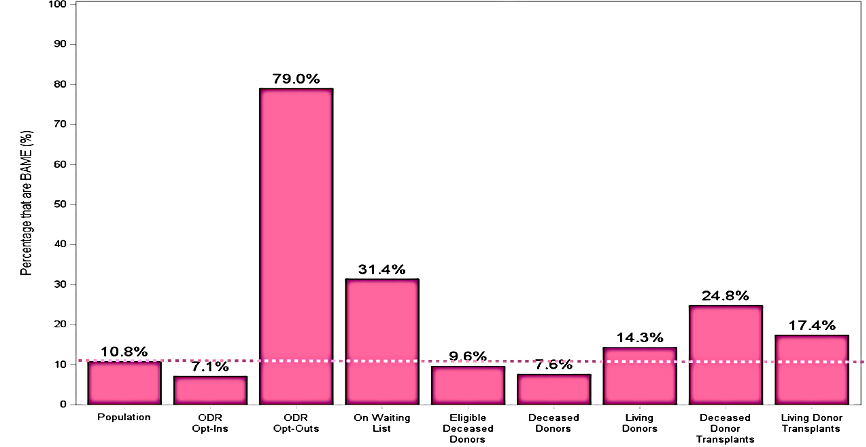

Approximately 1,800 BAME patients in the UK are currently waiting for organ transplantation. Despite nearly 14% of the UK population being classified as BAME, only 8% are actually registered donors on the Online Donor Registry (ODR) [9]. However, a large proportion of unreported/ unknown ethnicity (67%) on ODR is major limitation to draw definite conclusion. The number of BAME deceased organ donors has increased by 51% over the last 5 years, from 80 in 2014-15 to 121 in 2018-19. In 2018-19, ethnically Asian people represented 4% of deceased donors (DD), 13% of DD transplants and 17% of the transplant waiting list; people of Afro-Caribbean descent represented 1% of DD, 13% of DD transplants and 11% of the list. White ethnicity is significantly over-represented in organ donor register.

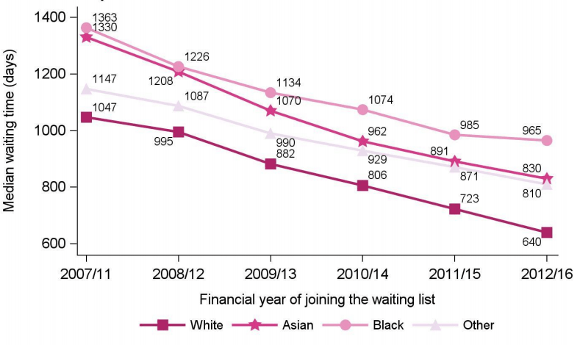

There is a real need for more people from BAME communities to donate organs either in life or after death. The compelling reasons include the ethnic variation associated with tissue type and blood group; the disproportionately high number of BAME patients on waiting list; and the longer time BAME patient spend already on the list waiting for an organ. Analysis of waiting list data shows that only 19% of BAME patients receive a kidney transplant within one year of being on the waiting list, compared with 31% of white Caucasian patients [9]. Overall waiting time has improved substantially in last decade (see figure 1) and the new allocation scheme from 2019 is expected to reduce further variation based on ethnicity [10].

Figure 1: Median waiting time for a kidney as per ethnicity in UK (adapted from ref 10)

Family consent for donation is much lower within the BAME community - 42% compared with 71% for white potential donors [5]. Although consent rates are increasing from donors of a BAME background, the new opt-out system is expected, along with change in allocation policy, to help a greater proportion of patients from BAME backgrounds.

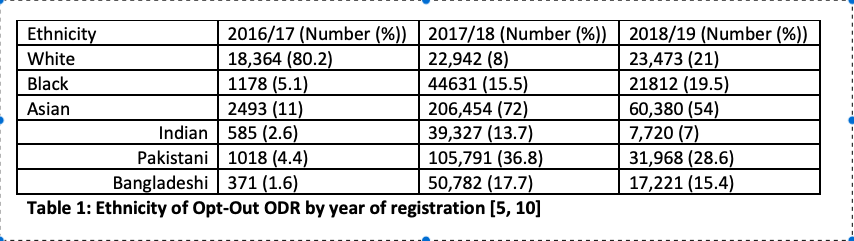

About 1% of UK population (N=640,435) have opted-out of the organ donation register [5, 10]. Relative to the UK population, there is over-representation (n = 118,000) of opt-outs among traditional BAME communities, in comparison to White and Chinese people. Around 54% of these opt-outs were made by Asian people in 2018-19 (Table 1). While it remains a fundamental right to opt out, the concern is that some individuals are making this decision based on misinformation, misplaced fear or misconceptions about faith beliefs.

Table 1: Ethnicity of Opt-Out ODR by year of registration [5, 10]

Figure 2: BAME Summary of representations at various aspects of organ donation and transplantation (NHSBT 2020) (Note: data with unknown ethnicity excluded for analysis)

What initiatives can BAME communities take?

Major religions support organ donation. Nevertheless, the most frequent reasons given by family members declining donation was either it was is against a patient’s religious or cultural beliefs (20-30%) or uncertainty of the patient’s wishes (12-14%) [5, 10] or how the body will be handle during organ retrieval surgery. BAME leaders and organisations now need to work in partnership with the NHS to improve community education, promote faith and cultural engagement including identify key opinion leaders to support awareness-raising campaigns.

Less than half of families agree to organ harvesting when they do not know the deceased’s last wishes regarding organ donation. However, rates increase to more than 9 out of 10 families when asked, if the conversation about organ donation had already been discussed with them prior to death. The body is handled with utmost respect and all procedures including analgesia and anaesthesia is performed by experienced surgeon and Anaesthetists respectively.

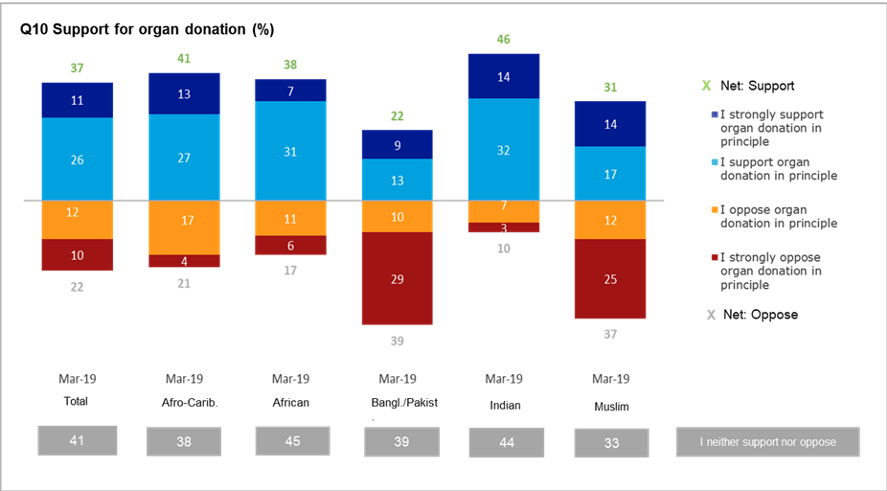

Majority of people opting in are of white ethnicity and elderly [11]. Attitudes towards organ donation among BAME communities vary depending on ethnicity (Figure 3). Recent data suggested shift in positive attitude with the number who would definitely donate some or all organs after their death has risen from 11 to 15 percent [12]. The data also suggests there is a real opportunity to focus on the significant proportion of people who remain undecided, targeting education around clarifying myths and misconceptions.

Figure 3: Attitudinal survey of black and Asian adults in England Survey carried out by Agroni Research Ltd 2019 [12].

Funding is available for BAME organisations to promote organ donation. Sources include the Community Investment Scheme Fund from NHSBT [13]. Other available support includes the NHSBT Organ Donor Ambassador programme, the National BAME Transplant Alliance (NBTA) and BAME charities such as South Asian Health Action (SAHA) and African & Caribbean Leukaemia Trust (ACTL). Community specific campaigns and events organised by SAHA have led to signing of many BAME donors. Similarly ‘Be the Hero’ campaign in Yorkshire has led organ donation promotion by community and public campaign. Individual families have also using social media campaign (such as Hope4Anya).

There are also examples of national steering groups helping to influence outcomes such as Jain Hindu Organ Donation (JHOD) who partnership with NHSBT and Local Assembly in London [14]. Despite 62% of Londoners waiting for an organ transplant being from BAME backgrounds, only 1% of BAME Londoners are registered on ODR [14]. Finally, BAME medical professional bodies such as British Association of Physicians of Indian Origin (BAPIO) and British Islamic Medical Association (BIMA) are now taking on the campaign to increase organ donation from BAME communities.

In conclusion, leaders of BAME communities through social events and digital campaigns can demystify the prevalent myths around organ donation and help fellow members with lifesaving organ transplantation. One donor can save up to eight lives and transfer up to 54 lives.

References:

[1] NHS Blood and Transplant. Keira's story - Max and Keira's Law. [Online] April 29th 2019. Available from: https://www.organdonation.nhs.uk/helping-you-to-decide/real-life-stories/families-who-donated-their-loved-ones-organs-andor-tissue/keiras-story-max-and-keiras-law/

[2] NHS Blood and Transplant. Organ Donation and Transplant Activity Data: UNITED KINGDOM. [Online] 2020. Available from: https://nhsbtdbe.blob.core.windows.net/umbraco-assets-corp/17582/nhsbt-united-kingdom-summary-report-dec-19.pdf

[3] NHS Blood and transplant. Transplant Activity Report Section 1 - Summary of Transplant Activity. [Online] 2019. Available from: https://www.organdonation.nhs.uk/helping-you-to-decide/about-organ-donation/statistics-about-organ-donation/transplant-activity-report/

[4] NHS Blood and transplant. Transplant Activity Report Section 2 - Overview of Organ Donation and Transplantation. [Online] 2019. Available from: https://www.organdonation.nhs.uk/helping-you-to-decide/about-organ-donation/statistics-about-organ-donation/transplant-activity-report/

[5] NHS Blood and Transplant. Transplant Activity Report Section 13 - National Potential Donor Audit. [Online] 2019. Available from: https://www.odt.nhs.uk/statistics-and-reports/annual-activity-report/

[6] Nugent et al; The Burden of Chronic Kidney Disease on Developing Nations: A 21st Century Challenge in Global Health; Nephron Clinical Practice 2011

[7] Nair et al, CARRS Surveillance study: design and methods to assess burdens from multiple perspectives. BMC Public Health. 2012 Aug 28;12:701.

[8] Kanaya et al; Mediators of Atherosclerosis in South Asians Living in America (MASALA) study: objectives, methods, and cohort description. Clin Cardiol. 2013

[9] NHS Blood and Transplant. Organ Donation and Transplantation data for Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) communities Report for 2018/2019. [Online] 2019. Available from: https://www.odt.nhs.uk/statistics-and-reports/annual-activity-report/

[10] NHS Blood and Transplant. More black, Asian and minority ethnic people are becoming organ donors, but shortage remains critical. [Online]. September 5th 2019. Available from: https://www.organdonation.nhs.uk/get-involved/news/more-bame-people-are-becoming-organ-donors-but-shortage-remains-critical/

[11] Catrin Pedder Jones, Chris Papadopoulos, Gurch Randhawa; Who’s opting-in? A demographic analysis of the U.K. NHS Organ Donor Register PLoS One. 2019

[12] Attitudes towards organ donation among black and Asian communities survey. https://www.organdonation.nhs.uk/get-involved/news/survey-reveals-shift-in-attitudes-towards-organ-donation-among-black-and-asian-communities/

[13] Community investment scheme for organ donation https://www.nhsbt.nhs.uk/how-you-can-help/get-involved/bame-funding-call/

[14] https://www.london.gov.uk/press-releases/assembly/only-1-of-bame-londoners-on-organ-donor-register