RESEARCH

Radial Artery Versus Saphenous Vein As Conduits In Coronary Artery Surgery: Comparison Of Intermediate To Long-Term Outcomes

Rajdeep S. Bilkhu, Anne S. Ewing, Vipin Zamvar

Department of Cardiac Surgery, Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh

cite as: Bilkhu RS, Ewing AS & Zamvar V. Radial Artery Versus Saphenous Vein As Conduits In Coronary Artery Surgery: Comparison Of Intermediate To Long-Term Outcomes.

The Physician 2012 vol1;issue1:22-26

Abstract

BACKGROUND AND AIMS

The radial artery has become an increasingly popular arterial conduit in coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG), however little data exists with regard to comparison of quality of life in patients undergoing CABG with radial artery grafts and those with conventional saphenous vein grafts. The aims of this study were therefore to identify any difference in long term quality of life in surviving patients between those undergoing CABG with radial artery grafts and those with saphenous vein grafts.

METHODS

Standardised questionnaires (SF-36 and Euroqol EQ5D) were sent to assess quality of life in 130 patients who had undergone CABG with venous grafts (Group A) and 130 patients who had undergone CABG with radial artery grafts (Group B). Information was also gathered to determine any angina recurrence following CABG in the patients included in the study. In addition, information on any major adverse cardiac events (MACE) occurring post-CABG was collected.

RESULTS

70 responses were received from Group A and 82 from Group B. The mean follow up time was 6 years in both groups. On analysis there was no statistically significant difference between both groups with regard to quality of life (based on SF-36 and EQ5D scores), angina recurrence or MACE.

CONCLUSION

Our study identified no additional benefit in using radial artery grafts over saphenous vein grafts with regard to quality of life, MACE or angina recurrence in the medium term.

Introduction

The advantages of arterial endothelium have resulted in the use of arterial conduits in coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG), and this has become an increasingly popular alternative to saphenous vein grafts (SVGs). This is largely due to low rates of recurrent atherosclerosis in arterial grafts, which consequently results in lower incidence of recurrence of symptoms of myocardial ischaemia.1, 2 The left internal mammary artery (LIMA) is considered the “gold standard” conduit in myocardial revascularisation due to excellent long term patency.1-3 The poor long term results seen with SVGs, and promising results seen with LIMA has led to the search for additional arterial conduits for CABG.4 The radial artery (RA) is being used more commonly as a conduit for CABG. Studies have demonstrated superior patency rates in patients receiving RA grafts over SVGs. 3,5 It is well known that vasoactive substances produced by arterial endothelium are protective and so are likely to have a role in the excellent patency rates of arterial conduits seen in those such as the RA.6, 7 Despite this, there is some angiographic data in early post-operative patients suggesting poor RA graft patency. This may be related to the spasmogenic nature of the radial artery.8 Indeed; it was noted soon after Carpentier et al first proposed the use of radial arteries for CABG in 1973 that spasm and occlusion occurred in these grafts.9 This led to the RA being abandoned before being introduced again in 1992 by Acar et al.9, 10 The benefits of the radial artery in the longer term should therefore be ascertained to determine its suitability as a potential alternative to venous grafting. In particular, the benefits on patients’ quality of life should be identified to help in determining the suitability of the radial artery as a conduit

for CABG. We therefore selected a sample of surviving patients in the period 2001- 2002 who underwent CABG and received RA grafts. We analysed their perceived health related quality of life (QOL) and any major adverse cardiac events (MACE) occurring post-CABG and compared this to data obtained from patients who had received SVGs at CABG in the same period. Data was also gathered relating to angina recurrence and further cardiac procedures performed after CABG such as percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Based on available data, it was hypothesised that those receiving RA grafts would report a higher quality of life, less angina, and fewer MACE than those receiving SVGs.

Methods

Ethical approval was obtained from the Lothian Research Ethics Committee. Between January 2001 and December 2002,11,12 patients underwent primary isolated first time CABG at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh. Of these patients 1073 had 3-vessel disease. Patients were divided into three groups depending on the conduits used for

surgery. Group A consisted of patients who received a LIMA graft and one or two SVGs. Group B consisted of patients who received a LIMA graft, and a RA graft with or without additional SVGs, as required. All other patients, who received only veins, bilateral mammary artery grafts, or other conduits were put into group C and excluded from the study. Group A consisted of 591 patients, and Group B consisted of 194 patients. Patients who died in hospital were excluded from both groups. Data was obtained from the Registry Office to exclude patients who died after discharge from hospital. Of the surviving patients, the first 130 in chronological order of

operation date from each group were selected for the purpose of this study. Patients in both groups were sent questionnaires to assess QOL. Standardised questionnaires, the EuroQol EQ5D and the SF-36 Health Survey were used. 11, 12 To assess for the presence of exertional chest pain, the shortened ROSE angina questionnaire was used.13, 14 In addition, a separate questionnaire was written to collect data on patients’ current medication, MACE occurring post-CABG and any strokes, angina recurrence, follow up percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or CABG and any pain from the conduit harvest sites or from the sternal wound. It was assumed those reporting higher health related QOL scores in the EQ5D and SF-36 questionnaires would be less physically and mentally restricted by their ischaemic heart disease and would have had a good outcome from their CABG. Similarly with angina recurrence and MACE, lower reported rates of these would suggest a more positive outcome overall and a higher QOL. Patients were asked to complete and return the questionnaires in the prepaid envelope provided. Those who did not reply were sent reminders after 3 weeks to maximise the number of responses. The replies received were then entered onto a spreadsheet and quality of life scores calculated.

Results

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

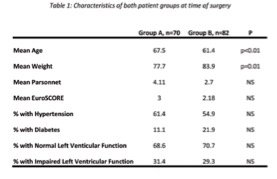

Data collected from questionnaires was stored on a spreadsheet and analysed using SPSS v13.0 for Windows.15 Continuous variables were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation and analysed using the student’s t-test. Categorical variables were analysed using the chi square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. 130 questionnaires were sent to each group. In group A, 46 reminders were sent and a total of 70 responses were received. In group B, 58 reminders were sent, and a total of 82 responses were received. Patients who did not respond were excluded from the study. Questionnaires were received from 152 patients. The calculated scores and totals for the domains assessed in group A (n=70) and group B (n=82) were then compared. The patient characteristics are shown in Table 1.

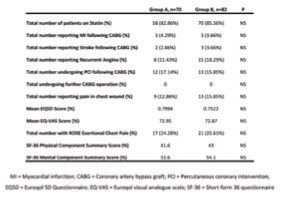

Results and comparison of the assessed domains is shown in Table 2.

MEAN FOLLOW-UP

The mean follow-up in Group A was 78 months, and in Group B, 72 months.

AGE and OPERATIVE RISK

Patients who received vein grafts, i.e. group A, were on average older than group B patients who received radial artery grafts, as shown in Table 1.

MAJOR ADVERSE CARDIAC EVENTS (MACE) & STROKE

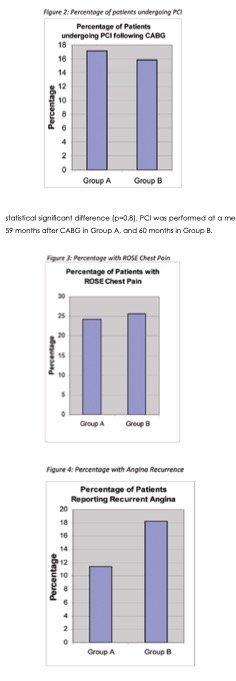

As shown in table 2, most patients in both groups were taking statin medication at the time of completing the questionnaire (83% and 85% in group A and B respectively). With regard to MACE, 3 patients in each group had suffered an MI (p=0.84) where as 2 people suffered a stroke in group A and 3 in group B (p=0.79) (See Figure 1).

No patients in either group underwent a further CABG operation.

PERCUTANEOUS CORONARY INTERVENTION (PCI)

12 (17.1%) in group A and 13 (15.8%) in group B had undergone PCI following their CABG operation (see Figure 2). However, there was no statistical significant difference (p=0.8). PCI was performed at a mean of 59 months after CABG in Group A, and 60 months in Group B.

ANGINA RECURRENCE and CHEST PAIN

In group A, a total of 8 patients (11.4%) reported recurrent angina where as 15 (18.3%) in group B had experienced angina following CABG (p=0.23). ROSE scores showed similar numbers of patients in both groups experienced exertional chest pain following CABG.13 (See Figures 3&4) 9 from group A and 13 from group B (p=0.18) complained of pain in the sternal wound. When reviewing comments made by patients, it was noted that most who experienced this described discomfort or an itch as

opposed to pain per se. Some patients complained of reduced sensation on the left side of the chest, correlating with the use of LIMA. A number of patients, particularly in group B, complained of itching and discomfort in the conduit harvest sites.

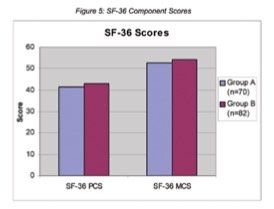

QUALITY OF LIFE

Health related QOL was assessed by administration of Euroqol EQ5D and SF-36 Health Survey.11, 12 After recoding, scores were calculated. The Euroqol EQ5D provided an overall score based on 5 separate health related questions, where as the SF-36 provided scores for a number of ‘health components’ based on the questions answered, which were then collated to give a physical component summary (PCS) score and a mental component summary (MCS) score. Group A patients had a mean EQ5D score of 0.7994 where as the mean for group B patients was 0.7522 (p=0.26). The mean SF-36 PCS score for group A was 41.6, whereas in group B a mean score of 43 was reported (p=0.54). MCS scores for both groups were similar; 52.6 and 54.1 for groups A and B respectively (p=0.36). Both groups scored consistently higher in the mental component score. (See Figure 5). As part of the EuroQol questionnaire, patients were asked to score their own health out of a total of 100 (the Euroqol Visual Analogue Scale or EQ-VAS). The mean scores (detailed in Table 2 as Mean EQ-VAS Score) for groups A and B were, again, similar. Results showed no statistically significant difference between group A and group B in relation to MACE, PCI procedures performed after CABG, angina recurrence or QOL. A statistically significant difference was noted with regard to patient age at the time of operation (p<0.01).

Discussion

Despite the increasingly popular use of the RA as a conduit for CABG, this study has shown no statistically significant difference in the long term with regard to health related QOL, angina recurrence or major adverse cardiac events between those undergoing CABG with SVGs and those receiving RA grafts. The results obtained are contrary to what we believed, as it was anticipated those undergoing CABG with RA grafts would report lower rates of angina recurrence, lower rates of MACE and a higher QOL. The results are somewhat contradictory to the popular conception that RA grafts are superior to venous grafts.10, 18, 19 Promising data from Shah et al demonstrated patency rates of RA grafts to be as high as 96% after 5 years, in a sample of 209 post-CABG patients. Certainly, others have confirmed similar findings.20 This has led to some considering the RA a second choice conduit after the “gold standard” LIMA. 21,22 In our study, all patients received left internal mammary artery (LIMA) to left anterior descending (LAD) grafts. Based on strong evidence from numerous studies, the LIMA has been shown to have particularly high patency rates.23-25 The LAD artery is the most important of the three coronary arteries, and grafting this with the LIMA is responsible for the majority of the beneficial effect of CABG operation. In our study we compared the RA versus SVG applied to the second and third most important coronary arteries. The possible additional benefit of using RA grafts was studied and showed no difference in QOL or angina recurrence. Although no specific studies have been conducted into QOL in this context, many have looked at angiographic data in patients who had received RA grafts and compared this to those who have undergone CABG with SVGs. Calafiore et al identified improvement in long term angiographic outcomes in patients receiving RA grafts as compared to those receiving SVGs and showed that vein graft patency was worse (91.7%) than radial graft patency (99%) suggesting a greater incidence of angina recurrence in those receiving SVGs.5 Our study is unique in that the comparison of health related QOL in patients receiving venous and arterial grafts is not well documented. Studies have looked at the effects on QOL post CABG and have demonstrated supremacy against medical treatment of coronary artery disease.26 Despite this there has been no specific study assessing QOL and comparing this in those who have undergone bypass with venous or arterial grafts. As mentioned, the QOL scores in both patient groups were similar. The difference between SF-36 health scores of both groups was not statistically significant, similarly with EQ-5D scores. Even with numerous studies demonstrating superiority of the RA over SVGs in terms of patency rates, this it appears did not translate to a higher patient perceived health related QOL in the RA group of our study. The similarity in results may be accounted for by use of LIMA, in that the use of this “gold standard” conduit may have had such a dominant influence on outcome in the studied patients due to its excellent long term patency, resulting in both groups experiencing similar results and therefore reporting similar QOL and to some extent, angina recurrence. As well as this, the length of follow up in the study may have had a role to play. In our study, the average follow up was 6 years and so an even longer follow up may have identified a more significant difference in QOL and in angina recurrence. With regard to the age of the patients studied, the mean age of group B was significantly less than that of group A. As patients in group A were older, it is likely that many of these patients suffer co-morbidities, such as musculoskeletal or respiratory disease and most likely this would produce a lower QOL score. As patients in group B were younger, this would not seem to account for the similarity in QOL scores observed as one would expect these to be higher than group A scores. This may suggest those in group B are more limited from their cardiovascular disease. However, as the number of those reporting angina recurrences and other MACE is similar, it would not seem appropriate to draw the conclusion that quality of life is lower than what one would expect in this group.

A limitation of the study is the relatively small sample size and that despite showing a marginal difference between both groups, this possible difference did not reach statistical significance to allow us to draw fully valid conclusions. A further, larger follow up study would be a suitable means of assessing any possible difference in QOL, angina recurrence and MACE. In addition, matching patients, particularly in terms of age may help to provide a more accurate assessment of quality of life

between both groups as the impact of illness and disease is highly likely to have an influence on the quality of life of a patient at different ages in life.

CONCLUSION

In summary, our results show that the use of the RA as a conduit for CABG does not confer any additional benefit over SVGs in the intermediate-tolong term with regard to QOL, angina recurrence or MACE. ■

Acknowledgements

Funding for this study was received from the Royal Medical Society, Edinburgh.

References

1. Okies JE, Page US, Bigelow JC, et al. The left internal mammary artery: the graft of choice. Circulation. 1984;70(suppl I):I-213–I-221.

2. Nwasokwa ON. Coronary artery bypass graft disease. Ann Intern Med 1995;123:528-545

3. Chowdhry TMF, Loubani M, Galinanes M. Mid-term results of radial and mammary arteries as the conduits of choice for complete arterial revascularization in elective and nonelective bypass surgery. J Card Surg. 2005; 20: 530-536

4. van Brussel L, Voors A, Ernst G, Knaepen J, Plokker M. Venous coronary artery bypass surgery: a more than 20-year follow-up study. Eur Heart J 2003;24(10):927—36.

5. Calafiore AM, DiMauro M, D’Alessandro S et al. Revascularisation of the lateral wall: long-term angiographic and clinical results of radial artery versus right internal thoracic artery grafting. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2002;123:225-31

6. Rang HP, MM Dale, Ritter JM, Moore PK. The Vascular Endothelium. In: Pharmacology 5th Ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2003. p. 286- 287

7. Egashira K. Clinical Importance of Endothelial Function in Arteriosclerosis and Ischaemic Heart Disease. Circ J 2002;66:529-533

8. Risteski PS, Akbulut B, Moritz A, Aybek T. The radial artery as a conduit for coronary artery bypass grafting: review of current knowledge. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg 2005;5:153-162

9. Carpentier A, Guermonprez JL, Deloche A, et al. The aorta-tocoronary radial bypass graft: a technique avoiding pathological changes in grafts. Ann Thorac Surg 1973;16:111-121

10. Acar C, Jebara VA, Portoghese M, et al. Revival of the radial artery for coronary artery bypass grafting. Ann Thorac Surg 1992;54:652-660

11. EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. The EuroQol Group. Health Policy. 1990;16:199-208.

12. Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36 item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992;30:473–83.

13. Rose G. The diagnosis of ischaemic heart pain and intermittent claudication in field surveys. Bull World Health Organ 1962;27:645-58

14. Rose G, McCartney P, Reid DD. Self-administration of a questionnaire on chest pain and intermittent claudication. Br J Prev Soc Med 1977;31:42-8

15. SPSS V13.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA

16. Parsonnet V et al. A method of uniform stratification of risk for evaluating the results of surgery in acquired adult heart disease. Circulation. 1989;79:I 3-12

17. S.A.M. Nashef, F. Roques, P. Michel, E. Gauducheau, S. Lemeshow and R. Salamon, European system for cardiac operative risk evaluation (EuroSCORE). Eur J Cardio-thorac Surg. 1999;16:9-13

18. Acar C, Ramsheyi A, Pagny J, Jebara V, Barrier P, Fabiani J, Deloche A, Gurmonprez J, Carpentier A. The radial artery for coronary artery bypass grafting: clinical and angiographic results at five years. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1998;116:981-989

19. Possati G, Gaudino M, Alessandrini F, Luciani N, Glieca F, Trani C, Cellini C, Canosa C, Di Sciascio G. Midterm clinical and angiographic results of radial artery grafts used for myocardial revascularisation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1998;116:10151021

20. Shah PJ, Seevanayagam S, Rosalion A, Gordon I, Fuller J, Raman JS, Durairaj M, Buxton BF. Patency of the Radial Artery Graft: Angiographic Study in 209 Symptomatic Patients Operated between 1995 and 2002 and Review of the Current Literature. Heart Lung Circ 2004;13(4):379- 383

21. FD, da Costa, IA, Poffo, R, et al Myocardial revascularization with the radial artery: a clinical and angiographic study. Ann Thorac Surg 1996;62,475-480

22. Manasse, E, Sperti, G, Suma, H, et al Use of the radial artery for myocardial revascularization. Ann Thorac Surg 1996;62,1076-1083

23. Loop F, Lytle B, Cosgrove D, et al. Influence of the internal-mammary artery graft on 10-year survival and other cardiac events. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:1–6.

24. Okies JE, Page US, Bigelow JC, et al. The left internal mammary artery: the graft of choice. Circulation. 1984;70(suppl I):I-213–I-221.

25. Cameron A, Davis KB, Green G, et al. Coronary bypass surgery with internal-thoracic-artery grafts: effects on survival over a 15-year period. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:216–219.

26. Favorato M, Hueb W, Boden W, Lopes N, Nogueira C, Takiuti M, Gois A, Borges J, Favarato D, Aldrighi J. Quality of life in patients with symptomatic multivessel coronary artery disease: A comparative post hoc analyses of medical, angioplasty or surgical strategies – MASS II trial. Int J Cardiol. 2007;1163 :364-370.

Tables & Figures

Early Results of ERAS (Enhanced Recovery After Surgery) Protocol in Orthopaedic Surgery

Jaydeep Shah MBBS, M.S (T&O), MRCSEd, FRCSEd (T&O)

Associate Specialist, Trauma and Orthopaedics, Princess of Wales Hospital, Bridgend

Keshav Singhal MBBS, M.S (T&O), MCh (Ortho), FRCS

Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon, Princess of Wales Hospital, Bridgend

cite as:

Shah J & Singhal K. Early Results of ERAS (Enhanced Recovery After Surgery) Protocol in Orthopaedic Surgery.

The Physician

2012 vol1; issue1: 28-32

PDF (Tables and Figures)

Abstract

Background

The concept of fast track (Enhanced Recovery After Surgery, ERAS) was introduced to colorectal surgery in Denmark by Kehlet in 1999 which improved the quality of the care and reduced the length of hospital stay following major colorectal surgery. The same principles of ERAS have been applied to the orthopaedic surgery particularly the hip and knee replacement surgery and fracture neck of femur surgery. It is a relatively new approach in orthopaedics to the preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative care of the patients undergoing surgery. we have compared the length of inpatient stay, day of mobilisation, postoperative blood transfusion and adverse outcome for the patients undergoing hip or knee replacement by a single surgeon (KS) between ERAS and NON ERAS patients.

Results

A total of 138 patients underwent hip or knee replacement, hip resurfacing arthroplasty or oxford unicompartmental arthroplasty between July 2011 and June 2012 with ERAS protocol. In the Non ERAS group, 140 patients underwent hip or knee arthroplasty, resurfacing or oxford unicompartmental knee replacement in the previous year (July 2010 to June 2011) by the same surgeon.

Average hospital in patient stay for the ERAS patients was 4.12 days with 73.10% of the patients having an inpatient hospital stay of less than or equal to 5 days. The average hospital in patient stay for the NON ERAS patients was 8.34 days with only 24.08% of the patients being discharged in less than or equal to 5 days.

Conclusions

Our study shows that the implementation of the ERAS protocol in hip and knee replacement surgery is associated with improved patient experience, faster recovery and shorter hospital in patient stay with no increase in complication.

Introduction:

Total hip and knee replacement are the commonest, most successful and cost effective orthopaedic surgical interventions. They provide reliable pain relief and marked improvement in the function of the patients suffering from Osteoarthritis or inflammatory arthritis of the hip or knee. 10 Typically a patient undergoing hip or knee replacement is admitted day before the planned surgery. Traditionally after the surgery, patient stays in the bed overnight with PCA (Patient controlled analgesia), drain from the operative site and an attempt is made to mobilise out of bed on 1st postoperative day. The average length of stay for a hip or knee replacement is between 5.4 days to 9.1 days for hip replacement, and between 5.3 to 8.1 days for the knee replacement. 7 with the Changing times and scrutiny of expenditure along with limitations/cuts on the public spending, more emphasis is put on the efficient use of available resources. At the same time the expectations of the public is increasing with increasing litigations. Reducing the hospital stay should reduce patient morbidity, free up much needed hospital beds and increase the capacity of the hospital.

The concept of fast track (Enhanced Recovery After Surgery, ERAS) was introduced to colorectal surgery in Denmark by Kehlet in 1999 which improved the quality of the care and reduced the length of hospital stay following major colorectal surgery.1The same principles of ERAS have been applied to the orthopaedic surgery particularly the hip and knee replacement surgery and fracture neck of femur surgery. This is a relatively new approach in orthopaedics to the preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative care of the patients undergoing surgery. It is a multi modality, evidence based approach to improving the quality of patient care after major surgery, with a selected number of individual interventions which, when implemented together, demonstrate a greater impact on the outcomes then when implemented as individual interventions. It is a multidisciplinary approach involving surgeons, anaesthetists, nurses, physiotherapists, dieticians and occupational therapists. 3

ERAS is a part of wales assembly government’s 1000 lives Plus campaign. Its aim is to improve the quality of care provided to the patients who undergo major surgery. By improving the quality in care, and reducing the harm it is also assumed that the hospital stay will become more efficient, thereby allowing hospital services to realise the benefits of the programme, through savings in bed days. It has already been shown to benefit patients undergoing colorectal, urological, gynaecological and orthopaedic surgery.3

The basic principles of the ERAS include:

1. Ensuring the patient is in the best possible condition for surgery

2. Ensuring the patient has the best possible management during and after his/her operation.

3. Ensuring the patient experiences the best possible rehabilitation, enabling early recovery and discharge from hospital, allowing them to return to their normal activities quicker. 3

The main aspect of ERAS programme in orthopaedic surgery are, day of surgery admission (DOSA), Carbohydrate loading, Anaesthetic management, local infiltration analgesia, avoiding surgical site drain, regular postoperative analgesia and minimising the risk of postoperative nausea and vomiting, early mobilisation.

Day of surgery admission (DOSA) has a benefit of reducing the potential for surgical site infection and reducing the post operative complications. This will also help patients spending less time in the hospital and ultimately provide improved capacity within secondary care. 3 Carbohydrate loading 12 hours and 2-4 hours prior to surgery has also been shown to reduce patient anxiety, reduce preoperative thirst, hunger, and postoperative insulin resistance. It promotes a more anabolic state leading to less post operative nitrogen and protein losses as well as better maintained lean body mass and muscle strength. Nygreet found improvement in insulin resistance with patients given carbohydrate loading and Melis demonstrated it preserved immune function post operatively. 3, 6

Anaesthetic management: The aim is to deliver safe and effective sedation and analgesia to the patient which does not hinder early mobilisation. For patients receiving general anaesthesia, the protocol is as under.

a. Premed analgesia pregabalin 150 mg one hour preop ( reduce dose to 75 mg if patient aged over 75 years, has renal impairment or low BMI): 27,28,30

b. Minimise/avoid opiates. Use short acting anaesthetics.

c. Intraoperatively patient receives,

d. 1 gm IV paracetamol,

e. a non steroidal anti-inflammatory,

f. 15-20 mg/kg Tranexamic acid iv bolus prior to tourniquet.3,25

g. Dexamethasone 8 mg (28,29,30)

h. 20mmol Magnesium Sulphate infusion during surgery (started prior to tourniquet) and to titrate rate to heart rate and blood pressure. 26

i. 1-2 litres of iv fluid

j. Intra/postoperative local infiltration analgesia by the surgeon. 22, 23, 24.

In our institution, we use 30 mls of 5% chirocaine with 1 ml adrelaline diluted with 70 mls of normal saline. For patients receiving spinal anaesthesia,

a. Premed as above

b. Spinal analgesia aiming at unilateral block wherever possible, and to use minimum dose of anaesthetic to reduce urinary retention and delay in motor function.

Local infiltration analgesia:

it gives good post operative pain control without limiting the mobilisation with evidence showing a decreased use of patient controlled analgesia (PCA) up to 24 hours postoperatively. 22, 23, 24 Avoiding the drains: Drains can affect patient’s ability to mobilise easily and can, therefore, raise a psychological barrier to patient’s active participation in their rehabilitation. Surgical drains have not been shown to reduce complications and can actually cause problems such as infection. Some believe that there may be occasional clinical indication for using drains. 3 Regular postoperative analgesia: Suggested analgesia post operatively is regular paracetamol and a non steroidal anti inflammatory agent (depending on patient medical history) administered regularly, despite patient appearing pain free. Additional analgesia for the break through pain in the form of tramadol can be given. Pain is often a barrier for early mobilisation. The aim is for the patients to be reporting a pain score of less than 2 on movements.

Minimising the risk of post operative nausea and vomiting (PONV):

PONV can be more stressful than pain and can come in the way of early mobilisation. Appropriate regular anti emetic should be prescribed routinely so is to be given at the first indication of symptoms. In our department, we have a low threshold of using ondansetron for prevention/ treatment of PONV.

Early enteral nutrition and optimal fluid management: (3, 6) Early oral or enteral feeding is associated with an improved clinical outcome and it has been shown to be safe and well tolerated. It is dependent on using appropriate anaesthesia and analgesia, nausea and vomiting prophylaxis and optimal fluid balance. Suboptimal fluid balance can impair the wound healing, affect tissue oxygenation, leading to prolonged hospitalisation. The best way to limit postoperative intravenous fluid administration is to stop intravenous infusion and early return to oral or enteral fluid therapy.

Early mobilisation:

Early mobilisation maintains the muscle mass, promotes muscle strength and reduces the respiratory complication. It also helps prevent development of deep vein thrombosis. The aim is to mobilise the patient out of bed on the day of surgery. At 2-3 hours postoperative time on return to the ward, the patients are encouraged to sit in the bed. If they feel better, they are encouraged to stand with Zimmer frame with the help of physiotherapist and nurse. Once they feel confident, they can walk to the toilet on the same day of operation. This gives confidence, sense of well being to the patient and motivation for mobilisation from the next day onwards.

Evidence for ERAS protocols in surgery is available from colorectal resections:

ERAS protocols have been shown to be associated with faster recovery and reduced length of stay in hospital compared with traditional colorectal resections. ERAS protocols were associated with 2.45 days shorter primary hospital stay and 2.46 days shorter total hospital stay. Morbidity was lower in the ERAS group. 6

Materials and method:

ERAS programme was introduced as a structured protocol in the department of orthopaedics in Princess of wales Hospital, ABM University health board, in July 2011. This comprised of

1. Pre operative education and assessment of all the patients, due to undergo hip and knee replacement, in the preadmission clinic lead by the consultant orthopaedic surgeon (KS) and consultant anaesthetist along with the arthroplasty nurse practitioner, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, and arthroplasty ward nurse 6 wks before the planned surgery. The patients are given information booklet for the new approach, what it involves and “what to expect”.

2. Minimal perioperative starving with preoperative carbohydrate loading at 12 and 2-3 hours before the surgery. All the patients are given 2 sachets of “preload” (a neutral tasting carbohydrate loading drink) on the day of preassessment; each sachet contains 50 grams of carbohydrate preload powder to be mixed with 400 mls of water and to be drunk over 15 minutes.

3. No routine use of the drains.

4. Routine thromboprophylaxis with an oral anticoagulant agent.

5. Multimodal analgesia

6. Local anaesthetic infiltration intraoperatively: (Solution made of 30 mls of 0.5% Bupivacaine, 70 mls of saline and 1 mls of 1:1000 adrenaline) 7. Regular oral non narcotic analgesia and anti emetic with minimal use of the morphinoid drugs.

8. Structured early- on the day of surgery- postoperative weight bearing mobilisation programme.

9. Early oral feeding

10. Early discharge on day 3-4 postoperative whenever possible.

11. All the discharged patients are contacted over telephone at 48 hours post discharge by an arthroplasty nurse practitioner about their general condition and whether they have any concerns.

We have compared the length of inpatient stay, day of mobilisation, postoperative blood transfusion and adverse outcome for the patients undergoing hip or knee replacement by a single surgeon (KS) over a period of two years. All the patients were given a diary to fill the questionnaire during their stay and they were collected on the day of discharge. The diary asked the patient about the severity of pain, nausea, vomiting, day of weight bearing mobilisation, overall satisfaction. The pain has been graded from 0 to 3, with 0 as no pain and 3 as severe pain. The data has been collected prospectively for the ERAS Patients, from July 2011 to June 2012. we compared the results with the patients who underwent hip or knee arthroplasty in a preceding year, (NON ERAS) from July 2010 to June 2011 retrospectively.

Results

In the ERAS group, a total 138 patients underwent hip or knee replacement, hip resurfacing arthroplasty or oxford unicompartmental arthroplasty from July 2011 to June 2012 performed by single surgeon (KS). 49 patients underwent total knee replacement, 44 total hip replacements while 31 underwent hip resurfacing. 2 patients underwent Oxford Unicompartmental knee replacement and 3 underwent revision hip replacement. 9 patients underwent simultaneous bilateral knee replacement.

In the Non ERAS group, 140 patients underwent hip or knee arthroplasty, resurfacing or oxford unicompartmental knee replacement in the previous year by the same surgeon (KS). 63 patients underwent knee replacement, 41 hip replacement, 35 hip resurfacing and one patient underwent oxford unicompartmental knee replacement.

Average hospital in patient stay for the ERAS patients was 4.12 days with 45.5% of the patients having stayed less than or equal to 3 days. 73.10% of the patients had inpatient hospital stay of less than or equal to 5 days. Average stay for TKR (total knee replacement) patients was 4.08 days, while bilateral TKR patients had an average stay of 4.8 days. The average hospital inpatient stay for THR patients was 5.4 days. The patients who underwent resurfacing had an average hospital inpatient stay of 3.7 days.

In the non ERAS group, the average stay of patients was 8.34 days with only 7.75% of the patients being discharged in less than or equal to 3 days, and 24.08% of the patients being discharged in less than or equal to 5 days. Average hospital inpatient stay for the patients who underwent TKR was 7.9 days without ERAS protocol, while the patients who underwent hip replacement had an average hospital inpatient stay of 8.36 days. The patients who underwent hip resurfacing without ERAS protocol had an average hospital inpatient stay of 6.17 days.

None of the patient under ERAS protocol was prescribed PCA (Patient controlled Analgesia-Morphine) routinely. They were prescribed regular paracetamol along with anti inflammatory (where it is not contraindicated) along with pregabalin. 55.6% of the patients felt that they had adequate pain relief postoperatively, while 44.4% needed top up pain relief in terms of morphine. 78% of the patients in ERAS protocol had not experienced nausea or vomiting postoperatively, while 14 % suffered only nausea and 4% had vomiting. 4% of the patients did not comment on their diary. The nausea, vomiting and pain scores are not available for the NON ERAS group of patients.

42 patients out of 98 who completed the diary walked on the day of surgery to the toilet full weight bearing, while none of the patients walked on the day of surgery in the NON ERAS group. None of the patients on the ERAS protocol required postoperative blood transfusion, while 14 out of 140 patients required blood transfusion

after the elective joint replacement surgery in NON ERAS group.

All the patients (100%) were very satisfied with the overall management starting from the day of preassessment clinic. Two patients on the ERAS protocol developed DVT –both TKR- one occlusive below knee DVT and one non occlusive below knee DVT. Three patients developed below knee DVT in a NON ERAS group of patients, and one developed PE. Two patients on the ERAS protocol developed wound problems, one with wound oozing and second patient had haematoma. Both settled down with conservative management. 5 of the NON ERAS group had wound oozing problem, which also settled with conservative management. There was no incidence of postoperative wound infection in both the groups. Two of the ERAS group patient dislocated their hips (after primary THR) following fall. One patient’s hip became stable after closed manipulation and abduction bracing for 6 weeks, while the second patient required revision surgery to augment the cup orientation. One patient on the ERAS protocol developed aspiration pneumonia following general anaesthetic for which he was treated in the intensive care for 3 days. He recovered completely.

Discussion and conclusion:

The comparison data shows significant decrease in the hospital in patient stay for the patients in the ERAS protocol as compared with the standard NON ERAS group of patients. The pain was better controlled and nearly 50% of the patients who have completed diary have mobilised full weight bearing postoperatively on the day of surgery. Earlier mobilisation on the day of surgery makes the impact of surgery psychologically less stressful and also imparts the sense of well being. Having walked on the day of surgery gives a confidence boost to the patients and they are more likely to be out of bed mobilising for next few days making early recovery, avoiding complication of bed rest and likely to go home earlier.

On average the patients undergoing hip resurfacing are much younger than the patients undergoing standard hip or knee replacement surgery and they have fewer or no associated medical co morbidity. This accounts for the faster recovery and shorter hospital stay for the patient after the surgery, which is evident on both, ERAS and NON ERAS, groups of patients. The overall patient experience of undergoing a major surgery was satisfactory with no increased risk of complications.

The current evidence and our study shows that the implementation of the ERAS protocol in hip and knee replacement surgery is associated with improved patient experience, faster recovery and shorter hospital in patient stay with no increase in complication. This will also result in reduced risk of hospital acquired infection, increasing patient’s confidence in the organisation.

Shorter hospital stay will free up much needed hospital beds, including ITU/HDU, where applicable, with a potential to treat more patients with the same resources leading to increased capacity for the trust and longer term tariff benefits. ■

References:

1. Kehlet, H and Morgensen T. 1999, ‘Hospital stay of 2 days after open sigmoidectomy with a multimodal rehabilitation programme British Journal of Surgery, Feb; 86 (2):227-30.

2. Modernising Care for Patients undergoing Major Surgery: www. reducinglengthofstay.org. 1000 Lives Plus:

3. www.1000lives.wales.nhs.uk

4. Urbach,DR and Baxter, NN. 2005. Reducing variation in surgical care. BMJ 2005; 330 :1401 doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7505.1401 (Published 16 June 2005)

5. Delivering Enhanced Recovery after Surgery: Helping patients recover better aftersurgery. http://tinyurl.com/y2qeplm (Accessed 26th June 2010)

6. Enhanced recovery after surgery programs hastens recovery after colorectal resections. Ned Abraham, Sinan Albayati. world journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery 2011 January 27; 3(1):1-6, (editorial)

7. National joint registry for England and wales : 7th annual report. 2010

8. Scott Beattie w, et al (2009), ‘Risk Associated with Preoperative Anaemia inNoncardiac Surgery’, Anaesthesiology; 110:574 – 81

9. AAGBI Safety Guideline (2010), ‘Pre-operative assessment and patient preparation, the role of the anaesthetist’, The Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland

10. Oxford textbook of orthopaedics and trauma 2002

11.http://hospital.blood.co.uk/library/pdf/INF_PCS_HL_011_01_Iron_ leaflet.pdf

12. www.transfusionguidelines.org.uk

13. www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Anaemia-iron-deficiency/Pages/ MapofMedicinepage.aspx

14. UK Prospective Diabetes Study, Diabetes Control and Complications

15. Trial www.lho.org.uk/viewResource.aspx?id=9776

16. Shourie S. et al (2007), ‘Pre-operative screening for excessive alcohol consumption among patients scheduled for elective surgery’, Drug and Alcohol Review, 26: 119–125

16. Dix P and Howell S (2001), ‘Survey of cancellation rate of hypertensive patients undergoing anaesthesia and elective surgery, British’. Journal of Anaesthesia, 86 (6):789-793

17. Goldman L and Caldera DL (1979), ‘Risks of general anaesthesia and elective surgery in the hypertensive patient’, Anaesthesiology; 50: 285–92

18. Ramsay LE, williams B, Johnston GD, et al (1999), ‘British Hypertension Society guidelines for hypertension management’, summary. BMJ; 319: 630–5

19. ‘The Health Promotion Action plan for Older People in wales’ (2004), Health Challenge wales, welsh Government

20. welsh Risk Pool (2005), ‘welsh risk management standards 2004-2005’, St. Asaph:

21. Local infiltration analgesia: a technique for the control of acute postoperative pain following knee and hip surgery. A case study of 325 patients. Dennis R Kerr, Lawrence Kohan: Acta orthopaedic 2008; 79 (2): 174-183

23. Efficacy of periarticular multimodal drug injection in total knee arthroplasty. A Randomised trial: Constant A. Busch, Benjamin J. Shore, Rakesh Bhandari, Su Ganapathi, Steven J. MacDonald, Robert B. Bourne, Cecil H. Rorabeck and Richard w. McCalden.: JBJS Am. 88:959-963,2006. Doi:10.2106/JBJS.E.00344

24. Pain control after total knee arthroplasty: A Prospective study comparing local infiltration anaesthesia and epidural anaesthesia: Martin Thorsell, MD; Petter Hoist, MD: Hans Christian Hyldahl, MD: Lars weidenhielm, MD: Orthopaedics 33 w, 75-80 (Feb 2010)

25. Anti Fibrinolytic use for minimising perioperative allogenic blood transfusion (review) 2007: Henry DA, Carsen PA et al: Cochrane collaboration

26. Magnesium as an adjuvant to postoperative analgesia: A systematic review of randomised trials: Christopher Lysakowski, MD: Anesth Analg 2007: 104: 1532-9

27. Gabapentin and postoperative pain: a qualitative and quantitative systematic review, with focus on procedure: Ole Mathiesen, Steen Moiniche and Jorgen B Dahl: BMC Anesthesiology 2007, 7:6

28. Pregabalin and Dexamethasone improves post operative pain treatment after tonsillectomy: O Mathiesen, D G Jorgensen et al: Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2011; 55:297-305

29. Single dose Dexamethasone reduces dynamic pain after total hip arthroplasty: Anaesth Analg: 2008: 106:1253-7

30. MultimodalanalgesiawithGabapentin,ketamineandDexamethasone in combination with paracetamol and ketorolac after hip arthroplasty : a preliminary study: Michael L. Rasmussen, Ole Mathiesen, Gerd Dierking et al: Eur J Anaeshtesiol 2010;27: 324-330

31. Low risk of thromboembolic complications after fast tract hip and knee arthroplasty. : Henrik Husted, Kristian Stahl Otte et al:Acta Orthopaedica 2010; 81 (5): 599-605